Society

10 min

By Maksymilian Szabatin

Dec 9, 2025

Introduction: The Pragmatic Dimension of Celebration

Every year on October 1st, China marks the anniversary of the proclamation of the People's Republic of China in 1949. Yet, for analysts, entrepreneurs, and observers of modern China, this date transcends mere historical commemoration. National Day is a phenomenon of multidimensional significance: a potent political instrument legitimatising authority and shaping national identity; a strategic economic engine driving mass consumption and tourism via the "Golden Week"; and an annual manifestation of national aspiration.

Personal Insight

This complexity is best observed in Shanghai, moments before the festivities commence. Twenty-four hours before "zero hour," the city gleams with unnatural order, its skyline illuminated with intensified brilliance. Red flags establish a visual code of unity, fluttering not only from administrative edifices but on virtually every street corner. Simultaneously, the metropolis bifurcates: while tourist icons like the Bund (Waitan) are paralysed by throngs of visitors, residential districts and university quarters retreat into a state of deep, local tranquillity. This dichotomy between official celebration and private quietude perfectly encapsulates the nature of contemporary China. To fully grasp why this single day exerts such profound influence—from global supply chains to consumer sentiment—one must examine its historical roots and symbolism, born at a pivotal moment on Tiananmen Square.

Section 1: The Road to Tiananmen – Historical Context

The proclamation of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949, was not an isolated event. It represented the culmination of over a century of upheaval, humiliation, and brutal conflict that forged the Chinese national psyche. The end of the Second World War in 1945 brought no peace; instead, the country plunged into the decisive phase of the civil war between the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) government led by Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist Party of China (CCP) under Mao Zedong.

The conflict, intermittent since 1927, reignited with unprecedented ferocity following Japan’s capitulation. The Communists, having built their support base in rural areas, gradually gained the upper hand over KMT forces, who dominated the cities. Between 1946 and 1949, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) seized control of key regions, leading to the symbolic surrender of KMT troops in Beijing in January 1949. By year’s end, the remnants of the nationalist government had evacuated to Taiwan.

Historical Context

However, to understand why the Communist victory was greeted with hope by many, one must view this moment through the lens of the "Century of Humiliation" (Bǎinián guóchǐ). This term describes the period from the First Opium War (1839) to 1949, during which a once-powerful empire was dominated by Western powers and Japan, forced into "unequal treaties," and stripped of territory and sovereignty. Following decades of internal chaos, warlordism, and the devastating war with Japan, the CCP's victory was perceived not merely as an ideological triumph, but as something far more fundamental: the end of chaos and the restoration of national dignity.

The promise of stability and sovereignty provided a powerful mandate, legitimatising the new authority. The proclamation of the PRC was framed as the definitive closure of the "Century of Humiliation" and the dawn of an era where China would finally stand on its own feet. This historical backdrop is key to understanding the current Chinese business mindset: the red flag symbolises Sovereignty and Order. The Party derives its legitimacy from delivering on the promise: "No more chaos". For international business, the signal is clear: China values stability and long-term planning over short-term gains.

Section 2: The Historical Moment – 1 October 1949

Precisely at 3:00 PM on October 1, 1949, hundreds of thousands gathered in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square to witness the birth of a new state. The central figure was Mao Zedong, who stood atop the Gate of Heavenly Peace—formerly a symbol of imperial power—to announce the founding of the People's Republic of China. His speech, though momentous, began with simple yet potent words: "Compatriots, the Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China has been founded today!". Mao declared that the "people's war of liberation has been basically won" and the nation liberated from "reactionary rule".

Following these words, the band played the new national anthem, and the new state flag—a red banner with five golden stars—was hoisted for the first time. This symbolic act was a visual confirmation of the new era. The ceremony concluded with a military parade by the newly formed PLA, designed to demonstrate the strength and discipline of the state. Although Soviet operators were invited to film the event in colour, a fire days later destroyed nearly all the footage. Consequently, the iconic imagery of the PRC’s proclamation remains largely black and white, adding a layer of historical patina.

Section 3: Symbols of a New Era – Flag, Anthem, and the Nation’s Heart

October 1, 1949, birthed not only a state but also new national symbols that remain central to Chinese identity and state ritual.

The Five-Star Red Flag (Wǔxīng Hóngqí)

The flag was designed to visually articulate the political structure and ideology of the PRC.

The Red Background symbolises the communist revolution and the blood of martyrs, whilst also being the traditional Chinese colour of fortune.

The Five Golden Stars represent the unity of the Chinese people. Their yellow hue symbolises "light" illuminating the "red earth".

The Large Star symbolises the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CCP).

The Four Smaller Stars represent the four social classes united under the Party: the working class, the peasantry, the urban petit bourgeoisie, and the national bourgeoisie.

The arrangement unequivocally communicates that national unity is possible only under the central leadership of the Communist Party.

National Anthem – "March of the Volunteers" (Yìyǒngjūn Jìnxíngqǔ)

The choice of anthem was a strategic decision to unify the nation around a respected symbol. Created in 1934 (lyrics by Tian Han, music by Nie Er), the "March of the Volunteers" was not strictly a communist song but a patriotic rallying cry during the war against Japan. Adopting it allowed the new power to embed this potent patriotism into the state's foundations. Its mobilising character is best captured in the opening verse: "Arise! Ye who refuse to be slaves! With our flesh and blood, let us build our new Great Wall!".

Tiananmen Square (Tiān'ānmén Guǎngchǎng)

The site of the proclamation underwent a fundamental transformation. From an imperial forecourt, it became the central public space of the new state—the symbolic heart of the nation. Expanded to accommodate mass rallies, it is the stage for the state's most critical rituals, most notably the daily flag-raising ceremony. Every sunrise, a PLA honour guard raises the flag in a precision march, a ritual that attracts crowds and serves as a daily reminder of state discipline and unity. These symbols form a cohesive system reinforcing the official narrative, linking patriotism with Party loyalty.

Section 4: Golden Week – Celebration in Motion

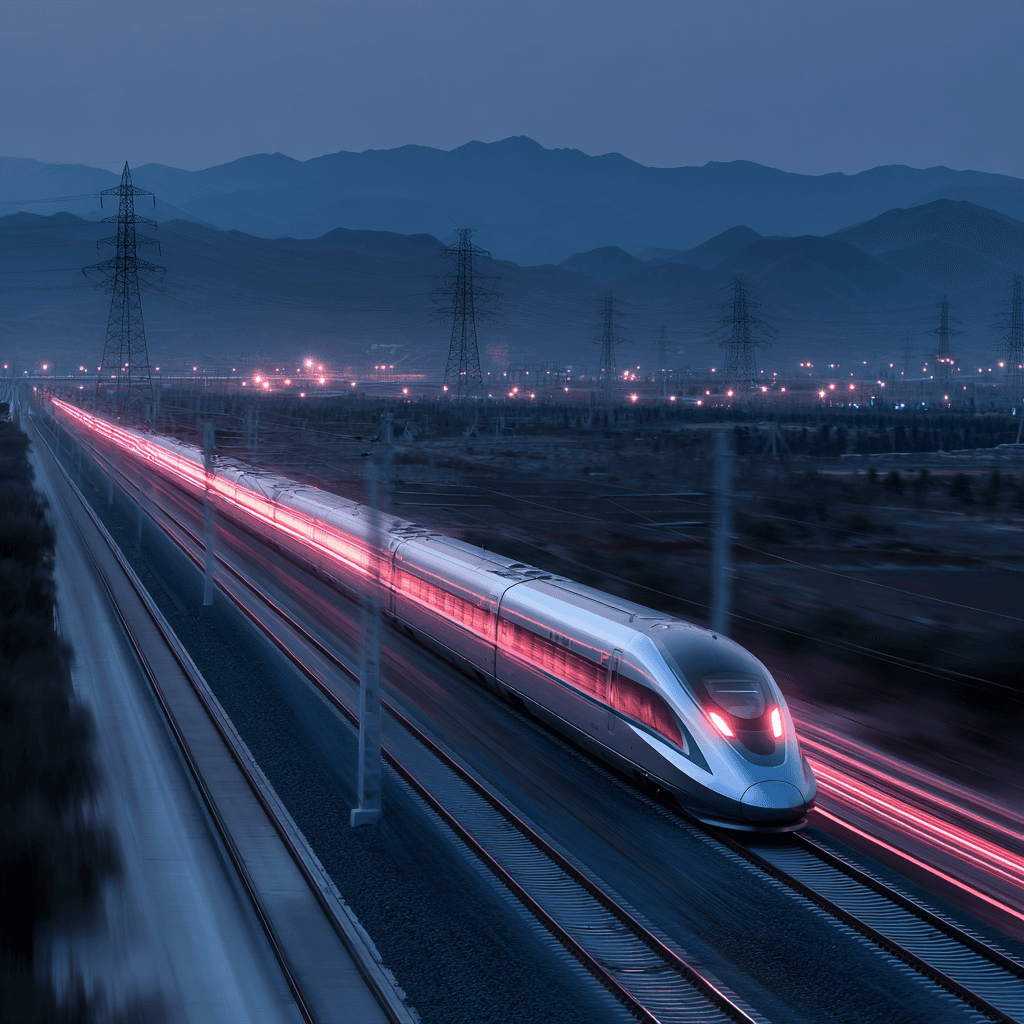

Today, National Day signifies far more than official parades. October 1st marks the commencement of "Golden Week" (Huángjīn Zhōu), a phenomenon that transforms a public holiday into a unique socio-economic event. Introduced in 1999 to stimulate domestic demand, it triggers the world’s largest annual human migration outside of the Lunar New Year.

During this period, hundreds of millions travel, visiting family or touring domestically and abroad. The scale is best understood not through statistics, but by witnessing the logistical mobilisation at hubs like Shanghai Hongqiao Railway Station. The transport system undergoes a massive "stress test" annually. For economic observers, the efficiency of these transport hubs is often a more reliable indicator of state capacity than dry GDP tables. From 28 million trips in 1999, numbers now regularly exceed 800 million. This mass movement generates immense revenue for tourism and retail, serving as a key government tool for economic stimulation.

Table 1: Golden Week Metrics – Consumer Sentiment Barometer

Metric | 2019 (Pre pandemic) | 2023 | 2024 |

Domestic Trips (millions) | ~782 | ~826 | 765 |

Domestic Tourism Revenue (bn RMB) | 649.7 | 753.4 | 700.8 |

Spending Per Capita (RMB) | ~831 | ~912 | ~916 |

Change in Spending Per Capita vs 2019 | - | +9.7% | -2.09% |

[Source: Data compilation based on research]

Analysis reveals a nuanced trend. While travel volume and total revenue have rebounded, surpassing 2019 levels, per capita spending in 2024 remained 2.09% lower than pre-pandemic figures. This indicates a cautious consumer who travels willingly but controls budgets. Concurrently, there is a structural shift in spending: less interest in luxury goods, more in local experiences and services.

Forecasts for 2025 suggest a continuation of these trends. Analysts anticipate record numbers, providing a crucial impulse for achieving the 5% GDP growth target. The 2025 Golden Week will be exceptionally long (8 days) due to alignment with the Mid-Autumn Festival, likely boosting long-haul and outbound travel. Interest in visa-free destinations and premium segments (business class, private tours) is expected to surge. Thus, Golden Week serves as an annual test of infrastructure resilience and a vital pulse check of the Chinese economy.

Section 5: Media Narratives – A Tale of Two Perspectives

The portrayal of National Day diverges radically depending on the observer’s vantage point, creating a distinct "narrative gap".

The Chinese Perspective

State media, such as Xinhua and CCTV, frame National Day as the culmination of national pride and unity. The dominant narrative focuses on the "Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation" under the CCP and President Xi Jinping. Coverage highlights technological prowess (e.g., greetings from taikonauts) and economic prosperity via Golden Week data. Military parades are presented as proof of a modern army safeguarding national sovereignty. The evening televised galas blend artistic performance with subtle political messaging to reinforce unity.

The Western Perspective

Western media view the event with analytical distance, focusing on geopolitics and economics. Military parades are scrutinised for new weaponry—hypersonic missiles (DF-17), drones—interpreted as strategic signalling towards the US and Taiwan. Economic data becomes a battleground for interpretation. European reports often emphasise "economic slowdown". However, the reality in Shanghai’s bustling malls suggests a more nuanced Darwinian competition rather than simple stagnation. The myth that "the Chinese consumer has stopped buying" is imprecise; rather, the structure of spending has evolved. What is celebrated in Beijing as a triumph over humiliation is often interpreted in the West as a manifestation of military ambition and a challenge to the global order.

Conclusion: A Living Holiday Shaping the Future

October 1st is far more than a calendar date; it is a dynamic phenomenon actively shaping China’s identity, economy, and society. Politically, it reaffirms the CCP’s legitimacy based on ending the "Century of Humiliation". Economically, via Golden Week, it acts as a mechanism for internal consumption and a barometer of health.

For business, the lesson is pivotal. China in 2025 is a market where mere "Westernness" no longer guarantees success. To compete with dynamic local brands (Guochao), foreign products must offer unique quality and deep localization. The sea of red flags on October 1st is not just a nod to a revolutionary past; it is a declaration of the present and a manifesto of future aspirations.